The biggest issue in wall cavities is when the wall wasn't originally designed for it.

You didn't say what type of foam, and it matters.

There are two types of foam. Open cell allows both vapor and moisture to pass through it. This is the least likely to change how the wall "operates" vis-a-vis your current insulation (none) does the same thing. Closed-cell completely seals the space, stopping all air and vapor movement.

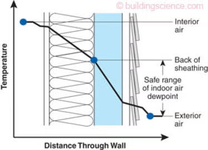

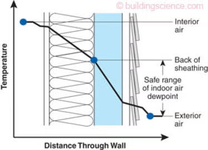

Humidity moves from higher to lower, like heat. In nearly all climates, it moves both directions - one way in winter and the other in summer. This happens even if you don't think of where you live as having a true "dry winter" (Florida) or "humid summer" (Colorado Rockies). Normally this is, and stays, a vapor, and it isn't a problem. The problem comes with what's known as the "dew point" in the wall:

With no insulation, your dew point is nearly always the interior drywall or exterior sheathing depending on the season. Moisture will condense there, which sounds bad but is actually normal - IF it has a way to dry out. Drywall is actually vapor open, even with latex paint on it, so a wall can "dry to in". And your sheathing is designed to shed water as well, and modern wall systems also include a "WRB" layer that additionally can shed this moisture. So no problem so far.

When you add insulation, you change the dew point curve, and move the "point" either inward or outward. With something like a dense-pack cellulose (which would also be my choice, as others have mentioned) that is very vapor-permeable, so if moisture now start condensing inside it, it can still dry out either direction with no problem. The same is true of rock wool and other common types.

The problem with foam depends on its type:

1. Open Cell is vapor open and can dry both directions. However, it acts like a sponge, holding water easily and even transporting it if you have a leak. Other insulation types can do the same thing, but open-cell "wicks" - it can draw moisture potentially several feet from a leak, and hold onto it a lot longer, making it "soggy". So although it can still dry (and is still the best choice IMO for a retrofit wall installation) it can still lead to mold growth and structural rot if you have a leak. It's important with open-cell to be sure your exterior sheathing and cladding are solid, leak-proof, and in good condition.

2. Closed Cell is air- and vapor-closed and will not transport moisture at all. In a new construction build this can be an advantage. A 1-inch "lift" of closed-cell is often used to air-seal a wall, which completely eliminates all drafts. (It's expensive, so frequently they stop here and use a traditional insulation to fill the rest of the cavity.) But this works in new construction because it's also commonly paired with exterior continuous insulation (typically some type of foam board or mineral wool). That moves the dew point even further "out" in the wall assembly. If done right, moisture won't condense on the foam. If done wrong, moisture will condense exactly there and have no way to dry out at all (because the foam itself prevents that). That gives you mold growth and sheathing rot, or worse.

You may not realize this but spray foam is an inexpensive, decent-margin business to get into - you just need a van, the spray equipment, and you can buy the foam in 55-gal drums. Businesses you can get into for $5k-$10k are the exact ones where you find fly-by-night operators who don't care what happens inside your wall in 10 years, and that's the rub - you won't have a problem in year 1. It's accretive - it'll be years before you have a problem and they'll be long gone by then.

If you decide to proceed with the foam I strongly recommend asking what type of foam they plan to install. Find out how long they've been in business. And ask them how their install will change the "dew point" in your wall. If they look confused or say "we've never had a problem before", run away.