By Matt Wymer, Rokslide Moderator

As you make the last push up the hill, a sense of satisfaction is felt. Your route planning panned out and your predetermined camp location is just a few minutes away. As darkness encroaches you quickly establish camp, chow down, and climb in the tent. You notice that the temperatures are dropping. You slide into your sleeping bag looking forward to the warmth it will bring. After a few hopeful moments you realize that cold is now invading your bag, starting at your toes and slowly moving its way up. You continue to add layers, until you are practically wearing all that you have hauled up the mountain, but it is not enough; a long cold night is ahead. You glance at your tiny thermostat frustrated to see that the temperature is registering more than a few degrees higher than the sleeping bag temperature rating. This bag should have done the trick!

This was me, on my first two sheep hunts in Alaska. The first hunt, I blamed myself for just not being tough enough, but after the second hunt I knew my sleep system was not adequate for what I was trying to do. The 20 degree rating on the sleeping bag I had did not translate to reality (both of these years it barely got below 30 degrees). Either I slept cold, or my system was not adequate for my pursuit.

Unfortunately, this is all too common. There are many variables that encompass how warm we sleep. In reality, the sleeping bag temperature rating is just one small component of the total sleep package needed to ensure a comfortable night’s sleep. Complicating matters is that there is no standardized method of rating sleeping bag warmth. While testing standards do exist, manufactures have a variety of rating options to choose from. So, what are they? And more importantly how do they differ?

Sleeping Bag Temperature Rating: A Moving Target

One of the most difficult product reviews to do is sleeping bags. Fit and temperature comfort ranges are very personalized, and reviewers must do their best to explain the process behind the review in order for the reader to personalize the end results. In my opinion these reviews are best used to help determine sleeping bag quality and customer satisfaction. As such, this article is an attempt to summarize, and explain, the processes behind Temperature Testing and Ratings.

The European Norm (EN) 13537 standard is used to exclusively rate hooded sleeping bags and is the standard for all hooded sleeping bags sold in Europe. EN 13537 is a calculation that translates insulation levels to a temperature range. In 2016 ISO EN23537:2016 (ISO 23537-1:2016) superseded EN13537 and is now considered the global standard to strive for. For a 2016 standard, there is not a lot of information out there on how it is being used, how it differs from 13537, and what the process is. You can purchase a copy of the standard, but little else is readily available.

Taking a step back, the ASTM standard was a USA based rating designed to allow for controlled comparisons of material performance. The problem with the ASTM standard was that it really wasn’t designed to provide a specific temperature rating. Numbers that came out of the tests were extremely subjective and resulted in inconsistent bag ratings.

Both the EN13537 and the ASTM sleeping bag temperature rating standards have specific requirements/standards for testing. Basically it involves a putting a sensor loaded heated manikin into a sleeping bag. The contraption is then put into a temperature controlled environment (aka a cold box) on a basic foam sleeping pad. The manikin is dressed in what the test describes as standard sleeping attire: a thin base layer.

As temperatures in the cold box change, measurements are read from the manikin. The test is designed to capture data points that show when heat builds up in the sleeping bag, at what temperature the heat seems to stay consistent, a range at which heat appears to dissipate, and finally the temperatures at which heat is lost to the point where the bag is not capable of keeping the manikin warm.

This data is then used to calculate a variety of comfort factors and heat ranges. The EN Test differs from the ASTM in that it includes standards for both males and females. A key point to consider is the definition what a “standard” male or female is. The standard male is defined as 5 feet 6 inches tall, 160lbs, and 25 years old. The standard female is defined as 5 feet 2 inches tall, 132lbs, and 25 years old.

A current trend seems to point to mass and density as key drivers in one’s ability to produce and retain warmth, and from what I can tell the testing standards do not account for this hypothesis. My mass and density is certainly different than the EN standard! Some argue that the way a female’s body superiorly distributes fat also plays a role in sleeping warmth, and supports the notion that women should buy bags designed for women.

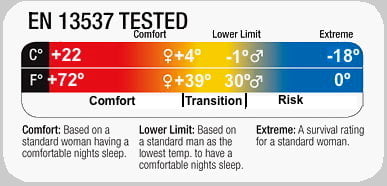

It is not clear to me how the ASTM outputs were used to derive ratings, which might explain the broad range of results. The EN13537 standard is shown as a subjective range of temperature where one might sleep comfortably. This range can be useful in comparing sleeping bags. Below is an example of such a range. The example articulates the perceived comfort change as you move through the range.

Comfort Range

According to the EN standard for the comfort range, the standard female is able to sleep comfortably at this temperature. My assumption is that this would be pretty good place to be for a night’s sleep. I find it odd that the standard lists women on the extreme right and left, and a man in the middle. I personally think the standard should be sex specific and two ranges should exist, one for men and one for women. Especially if the differences in body types contribute to sleeping comfort levels.

Transition Range/Lower Limit

In the transition stage, a standard man is in a situation of combating cold. He could even be curled up inside the sleeping bag for warmth. However enough warmth is there that he is not shivering or struggling hard to maintain warmth. This example shows that this Transition Range is also referred to as the Lower Limit.

Extreme /Risk Range

The EN standard states that in the Extreme Range strong sensations of cold are expected. In this scenario there is increased risk of hypothermia, or a miserable night’s sleep to say the least. For most of us, this would be an unplanned sleeping bag adventure, or dare I say an emergency scenario.

So using the chart above, what temperature would you put on a sleeping bag in that range? Would a manufacture do the same? Only way to tell is to look for a similar test result via the product specifications. However, my research shows very few companies actually provide the range chart. They simply state a temperature rating and that the bag is EN tested. Ideally they should list the EN standard used for their test and provide the results via a range chart. They should then state the point in the range they are using to rate their bag.

Some manufactures will provide a sleeping bag temperature rating, a limit, and a comfort temperature to compare. In my research I found one company that listed a specific sleeping bag as a 15 degree F bag. Digging into the specifications, the comfort rating was 30 degrees F. For me personally, I would NOT take this specific bag if I expected 15 degree F temps. KUIU, for example, states that their rating is based on the low end of the EN Range. My assumption, if comparing this against the above chart, is that this is the section of the chart labeled “lower limit.” This is a helpful data point to have when comparing a KUIU bag to other options.

As you can see, the challenge for us as consumers is that despite standard testing, the results are simply ranges. How those ranges are used to determine a bag’s rating can differ between manufactures. Complicating matters is that the standards used in testing are not reflective of real word scenarios. For most of us field conditions change, and often change quickly. Combine that with the intensity of the adventure, food intake, hydration levels, body makeup, and the external environment; and it makes for a real world experience far different that the lab based rating.

REI provides the following guidance on temperature ratings and is one of the leading consumer advocates to require EN Ratings for sleeping bags sold through REI.

Quote:

Temperature ratings on bags are a guideline; use your best judgment when choosing a bag to meet your needs.

How sleeping bags are rated: You may notice an “EN tested” tag on many 3-season backpacking sleeping bags. This stands for the European Norm (EN) 13537 testing protocol. The EN rating is internationally accepted as the most objective and dependable standard available, though not all bags use EN testing.

In EN testing, a bag is assigned two temperature ratings:

- Comfort rating is the lowest temperature at which the bag will keep the average woman or “cold sleeper” comfortable.

- Lower-limit rating is the lowest temperature at which the bag will keep a man or “warm sleeper” comfortable.

Everyone’s body and sleep comfort is different, so EN ratings are merely a guideline to help you compare products.

(EN ratings are based on a sleeper wearing one long underwear layer and a hat, and sleeping on a single one-inch thick insulating pad.)

Source: REI

This information from REI better helps one compare sleeping bags, and understand ratings.

Other Factors

Now that we have pushed through the technical details behinds ratings, we have to look at additional factors that play a role in sleeping comfort.

Other factors that add to the complexity are the fit of the bag, what clothing one wears to bed, and the type of sleeping pad used. All of these factors play key roles in calculating real world performance. Wind and dampness are additional factors that can greatly affect a quality night’s sleep.

My research seems to indicate that the EN standard for sleeping bag temperature rating is helpful, but only if used properly. My take is that one must understand the rating system, specifically the range of ratings, and then use it as a baseline to compare sleeping bags against each other. Reality means that it might take a few failures on our end before we find a bag that is tailored to how we sleep and intend to use it.

My conclusion is that we need to look at a sleeping bag as part of a total sleeping package. This package should include several factors, but starts with the combined performance of the sleeping bag and the mattress pad. Continuing down this path, it is critical to evaluate the fit of the bag. To tight and you compress the insulation and reduce its insulating capabilities. To loose and energy is wasted heating the dead space.

Another component of the sleeping system is clothing. Is there a dedicated set of sleep clothing, or do you utilize part of your outerwear to dial your system in? The final piece of the puzzle is the style of shelter (i.e tent, tarp, hammock, bivy, etc.) as the EN testing process assumes the sleeping bag is used in a tent. All of these factors combined make up your total sleeping package.

- Sleeping Bag

- Mattress Pad

- Overall fit of the bag

- Clothing worn in the bag (or not)

- Shelter Style

As we build this package it is easy to see the potential for variances. Each trip might require a custom tailored total sleep package based on the multiple variables each adventure requires. The weather and altitude are examples of external variables to consider as we build our system. Using the results of the tests, and comparing how manufactures use these results, helps us understand the baseline upon which to build a system. Nights in the bag prove our system and help us to better understand how the sleeping bag temperature rating can work for us, and in the conditions we use our system in.

In a follow up article I will explain how I used the results of my research to build my different sleep systems and how I tailor each of them to the adventure at hand.

You can comment on this article or ask Matt questions here. (Be sure and subscribe to that thread at “Thread Tools” top of post to receive a notification when part II publishes.)