No Service? No Problem!

By Chas Carmichael, Guest Contributor

My family worries about me being out alone when hunting – anything can happen from physical injury to a mechanical breakdown. My fear of rattlesnakes and ability to attract them is legendary, which adds to their worry. Verizon and Sprint don’t put cell towers where I antelope/deer hunt as prairie dogs and cholla don’t make reliable paying customers and the nearest population center is 40+ miles away in any direction. Other satellite-based technologies, such as SPOT/InReach and satellite phones, tend to focus on a specific solution to solve a specific problem and do that extremely well. Such a role-specific tool does not fit into our family budget or outdoor pursuits.

October 2015: Antelope hunting had been pretty rough in the plains unit of southeastern Colorado where I found myself hunting solo. Public land in the GMU is very sparse and weekend road warriors had done their due diligence in making sure the small antelope herds were well scattered and schizophrenic. Cell phone coverage just does not exist here. Adding insult to injury, I was having some health issues during the hunt. Nightly I checked in with my family, 107 miles away by road – 58 miles as the crow flies, via the amateur (HAM) radio installed in my camp trailer or a handheld unit in the field. Monday night, I reported to my wife via radio that I was coming back home the next morning (three days earlier than planned) as what I believed was a urinary infection was getting worse. The road warriors were all but gone so I decided to tough out one more hunt Tuesday morning after packing the trailer before sunrise. I was uncomfortable, but the discomfort was manageable at this point.

At daylight, I hobbled about a mile to my stand. At about 8:00 a.m. a lost doe pronghorn wandered within 300 yards and the H&R 25-06 did its job. A slow and painful walk to and from camp to get the game cart followed; there was no way that I could drag the antelope in my condition. By 9:30 AM, I had the doe hung, skinned, bagged, and in the trailer. Once on the interstate, I called my wife via cell phone and let her know I was on my way home and feeling pretty bad. That night I was in the local emergency room in the fetal position with complete urinary blockage due to a stricture (not infection). The ER doctor said I was unbelievably lucky that my bladder had not ruptured in the previous 24 hours and definitely would have ruptured in the next six if Nurse Helga—apparently trained by the School of Torture in Catheterization—had not intervened.

Without HAM radio, my ability to contact somebody and let them know I was in a potentially life-threatening situation would have been zero. Ever since my time as a forester and logger, I am in the habit of putting a map with my location on the fridge at home when I leave should somebody need to find me in an emergency. That information is worthless, however, if I need help now and people don’t come looking for me until after I miss coming home on a scheduled day. I need the ability to contact them when needed.

Use of any radio (or any communication device) when hunting varies by state so a careful reading of the regulations where you plan to hunt is critical and should be done annually to ensure compliance. In all states, using amateur (commonly referred to as HAM) radio to contact other HAM radio operators for information not specific to the pursuit and hunting of game (i.e. safety, general conversation), is legal. I am not going to dive into the state-by-state peculiarities of using a radio during the pursuit of game; communication outside of the actual pursuit of game is the focus here. I frequently use HAM radio when traveling to hunting and fishing areas, checking in with family from hunting camp to home, shed hunting as a group, ATV rides, and for communications between myself and any hunting partners or family back at camp.

Think about who else roams the high country of the western states and has needs for reliable communications. Search and rescue groups and wildland firefighters come readily to mind. Not surprisingly, both groups rely heavily on VHF (primarily) and UHF radios. The commercial band of frequencies are just above the HAM frequencies, but the radios are very similar in operation and power output.

Amateur radio solves many basic communications needs in remote areas at a very reasonable investment. You must be licensed by the FCC to use amateur radios. The basic Technician license required is not hard to obtain and gives you permissions on the VHF/UHF bands most useful for backcountry hunting. There are numerous free online resources for study (e.g. KB6NU Study Guides, QRZ Hamtest, QRZ Bookstore) and many others for purchase.

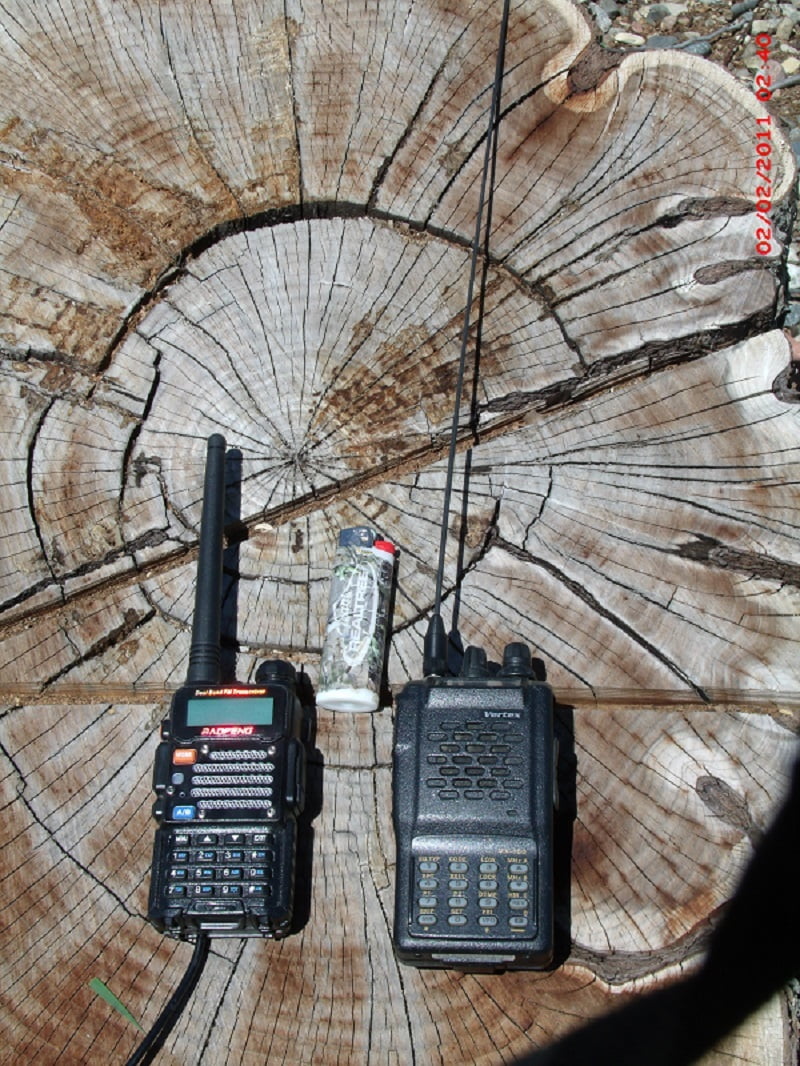

My wife and 14-year-old daughter both earned their Technician License after less than eight hours of online practice tests and study. Many HAM radio clubs also offer regular teaching sessions for individuals interested in HAM radio. After learning the material and making sure you regularly achieve about 80% on online practice tests, contact a local club (Find-a-club) and find out when they are offering testing in your area. Testing is $15, which the FCC charges for issuing the 10-year license, which is renewable (forever) for free without any additional testing. Portable VHF/UHF amateur radios range from $25 to $600 depending on the durability and features you desire.

Why go through all of that when you can go to Walmart and buy a two-pack of general mobile radio service (GMRS) radios for $39.99; Or, for $449.99 at Cabela’s you can buy an InReach for satellite texting capability? For me the answer is fourfold:

- Proven reliability in remote hunting environments as stand-alone units and using backbone infrastructure.

- After the initial purchase of an affordable radio, there are no other required annual fees or costs.

- HAM radio allows me more year-round applications and use at a more reasonable cost.

- In case of an emergency when cell towers are down or busy, I have an alternative source of communication and infrastructure to draw upon. While I do not have “instant call” emergency button for search and rescue, I do have the ability to contact others to notify them of a developing or emergency situation and they can talk to me in real-time.

Flexibility is a huge advantage of HAM radio over GMRS. According to FCC rules, you are required to be licensed to use the handheld GMRS radios. Family Radio Service (FRS) radio users do not have to be licensed according to FCC FRS rules but are restricted to very low power. Here’s the big difference though: FRS and GMRS radio allow the use of very few specific channels (assigned frequencies) whereas a licensed HAM radio operator may select any frequency within a broad range (or band) of frequencies encompassing thousands of potential channels (http://www.radioing.com/hamstart/hamfreqs2.html).

In application this means every hunter in the USA who is using a GMRS radio in an area are all using from the same small pool of channels. The odds of others using the same channel you want to use or listening to every word of your conversation is greatly increased. With amateur radio, changing frequencies is easy if traffic is heard on a selected frequency and different modes of operation can provide great privacy. There is so much bandwidth available, frequency conflict is rare.

Broad brush strokes here… Most common GMRS handheld radios have permanently affixed short antennas and are 0.5-5W (W = watts) output power. HAM handheld (portable) radios have longer interchangeable antennas and are 5-8W output power. Mobile HAM radios are generally 35-75W. More power equals better penetration of a signal. A better (longer and/or tuned) antenna equals better reception of poor signals and more effective transmit power. Just changing the antenna on a portable radio can create 2-4 times the effective power of the radio. In archery terms, transmit power would be equivalent to draw weight and the better the antenna the heavier the arrow. Combine increased draw and arrow weight and you have a recipe for excellent penetration in terms of effective power/communication.

Battery life is greatly dependent on how much transmitting you are doing. For example, if I’m checking in with my partner(s) four times per day and monitoring in the evenings until everybody is back in camp, I can generally get four days of use from a single battery. Carrying a spare battery is of negligible weight and doubles that time to eight days. If using a unit constantly during the day in other outdoor activities (shed hunting) I can get 12-16 hours of use from a portable radio (and avoid the comedic scene of two people in camo trying to communicate with hand signals a ½ mile away from each other).

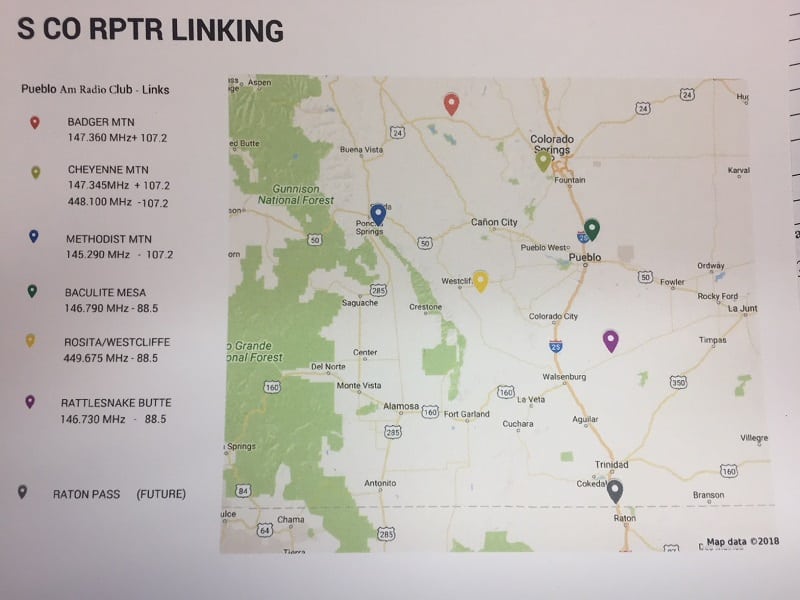

No annual fees! I don’t need a SIM card, a usage plan, a certain carrier. If whomever I want to talk to has an amateur license, is within simplex or repeater range, and has a radio capable of transmitting and receiving the same band/modulation as I have, all things are good. In many states, Colorado being one such location, new networks of digital repeaters are being installed allowing users to easily communicate from Raton to Wyoming using repeaters linked together, and all for FREE! Some repeater systems are also linked directly into the internet, so you can easily communicate with a family member 1,000 miles away if you are talking to a linked repeater and who you are talking to has a license and access to the internet. Many of the new digital formats being used by HAM operators are not able to be decoded by individuals with commercially available scanners, adding a layer of privacy if that is important for your needs or keeping your honey hole secret from other hunters. Stopping by a local HAM club meeting will answer all your location specific questions.

What is a repeater?

A repeater transmits on one frequency while receiving on another frequency. The advantage here is that most HAM radio repeaters are located at remote high elevation areas and designed to cover large geographic areas. My portable radio does not have to be strong enough to reach another radio many miles away, only strong enough to reach a nearby repeater which will then repeat the signal from my portable radio at a much higher power to another radio. As long as whomever I am trying to contact can reach the same repeater (or a repeater linked to the repeater I am using) we can communicate. These backbone systems are typically well maintained by local HAM radio clubs and use of a club’s repeaters is generally not restricted only to club members.

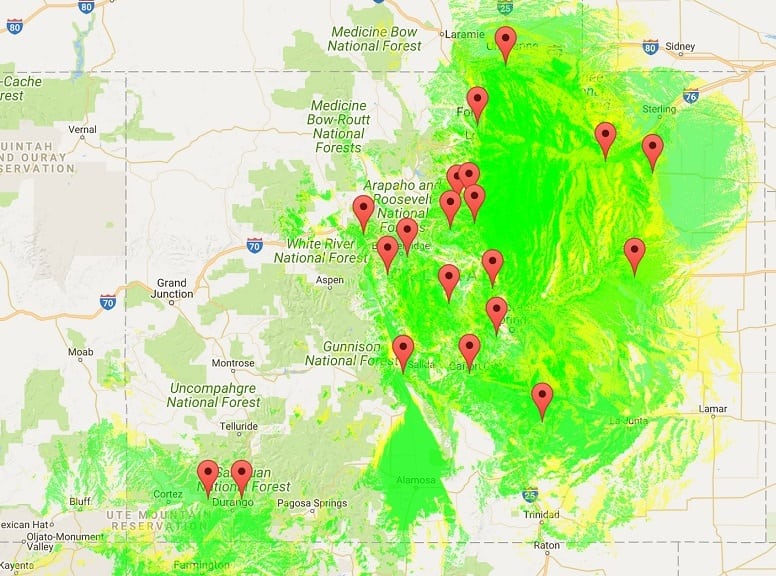

I use radio-to-radio (simplex) communication when talking to my hunting partner/camp in the field and repeaters for reaching far beyond the hunting area back to home. The ARRL Repeater Directory or online resources (e.g. TheRepeaterBook.com) can help you quickly identify repeaters in a general area. I did a quick search of amateur repeaters, open to any licensed amateur operator, within 25 miles of some major “hunting towns” and found 16 near Pagosa Springs, three near Gunnison, and eight near Vail. I am confident almost any hunter in the Colorado high country can hit an amateur radio repeater from their hunting area, especially in the high country. Every state in the USA has amateur radio repeaters designed for wide area local coverage. Using a repeater means I do not have to be within line of sight of camp or near who I am trying to reach, both parties only need to be able to reach a repeater, usually at a high elevation, often miles away, which (generally) transmits at 10-50 times the power of my original signal. A local amateur radio club can tell you all you need to know about their repeater’s coverage areas.

As a solo hunter, I want the ability to call for help when I need it wherever I am at. Every search and rescue team I have had contact with has members who are HAM operators or liaisons with local operators. In addition to knowing where I am supposed to be at, if necessary a searcher now has a means to contact and converse with me wherever I am at in the area. Ham radios operators typically scan the local repeaters in an area so even if you don’t have a designated contact person there is very likely somebody monitoring the repeater to help in an emergency.

On one hunt in Gunnison basin, I arranged with a local HAM operator to monitor a repeater, “an hour after dark” each night, and pass on any information I needed if I could not contact my family via intermittent cell service. This helped me focus on the hunt.

HAM radio is an incredibly diverse topic and this article covers only some of the basics of “short-range” VHF/UHF communication. The opportunities to experiment with other modes and applications is limited only by your imagination. Like any aspect of a hunting trip, communications planning to achieve the desired result is the key. Pick your area, find the available HAM resources in the vicinity, proof operation when scouting, and execute with success during the hunt following state-specific rules. HAM radio has proven to be an effective tool for my family, and I invite you to join the amateur radio outdoors community!

You can ask Chas questions or discuss this article here.

Chas. T. Carmichael is a Colorado native who has explored hunting and fishing throughout Colorado and occasionally ventures into Utah and Idaho. He has taken mule deer, elk, pronghorn, and whitetail deer in his adventures with bow, muzzleloader, and rifle. Currently the Service Manager at a two-way radio shop, Chas. has a B.S. in Natural Resources Management and a M.S. in Forestry and Wood Sciences, both conferred through Colorado State University – Fort Collins, CO. Just last year, Chas was recognized as a Commissioned Pastor within the Pueblo Presbytery, PCUSA, and serves in the Youth and Young Families Ministry at his current church in Pueblo, CO. “Boots on the ground” has been Chas.’ motto in the outdoors. Whether hunting, fishing, or running game cameras, he credits any success to a strong Christian faith and ample time spent outdoors with his family. Chas.’ passion is for finding less pressured “fringe” areas where game may be more sparse but other hunters are far less abundant. A decade of health issues now behind him, Chas. rekindled a renewed dedication to his love of the outdoors and is beginning a process of replacing tried-and-true older hunting equipment with newer equipment in an effort to go deeper, hunt smarter, and stay longer when he escapes into the woods.