Long Range Shooting: What is your maximum effective hunting range?

by Doug Rosin

When I first started rifle hunting about 20 years ago, determining maximum effective range was much easier. I started with a rifle I purchased over the counter, shot factory ammunition, used an average scope and below average binoculars. With that, I sighted in my rifle at 300 yards and tried to stalk as close as I could to my game before squeezing the trigger. I was moderately successful this way.

As the years went by, technology was rapidly advancing in all aspects, but certainly as it pertained to long-range hunting. Factory rifles were closing the gap with custom rifles, riflescopes were improving, every big optic company was making laser range finders, and many more people were starting to talk about taking game at long-range.

Long-range shooting is a topic that can divide a room full of hunters. There are those who believe it is unethical to shoot game at long-range and those that believe it can be done ethically with the right equipment and practice.

I am not going to try and sway your opinion one way or the other. I respect both sides and believe every hunter needs to make his own decision on what their maximum effective hunting range should be.

If you’re going to get into long-range shooting there are some things you need to know and specific equipment that will be needed to be effective. Long-range shooting can’t be done with every rifle, every caliber, or by everyone. This is a starter guide for getting yourself set up.

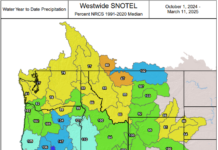

Long Range Country

The Rifle

Your rifle under the most ideal situation should be custom built by a reputable gun maker. Custom rifles usually come with a high price tag and many hunters just can’t afford them in today’s economic times. There are now many gun manufactures producing semi-custom rifles and stock rifles that are capable of being long-range producers.

There are different schools of thought about whether you should have a rifle that is light weight or one with more mass to reduce the recoil of larger calibers. Most quality built rifles, whether light or heavy, will shoot well if you take the time to set them up correctly.

I have a custom built .270 Weatherby Magnum that is ultra-lightweight and a custom .300 Jarrett that is on the heavy side. Both of these rifles shoot ½ minute of angle (MOA) per 100 yards out to 800 yards.

The Caliber

Once you’ve chosen a rifle, you need to find a caliber that is capable of shooting long-range. You also need to look at what bullets are available in that particular caliber so you can experiment with what works best out of your particular rifle. I personally think the 6.5mm or 7mm are the smallest calibers I would go with for long-range big game hunting. Pick a caliber that will adequately handle the animals you are hunting.

The Ammunition

Bullets are as important as any component in your equipment for long-range shooting. Although you may not know what bullet you will use initially, if you have a good rifle and have chosen your caliber wisely for the type of game you will be hunting, there should be several quality bullets to choose from. Remember rifles are very specific in nature and you will need to experiment to find the best overall finished cartridge that your rifle will drive tacks with.

When choosing a bullet, there are certain features you need to pay close attention to. The most important for long-range is the ballistic coefficient (BC). Ballistic coefficient is a measure of how streamlined the bullet is as it cuts through the air. Without getting too technical, just know the higher the BC the less drag and the more efficiently the bullet will perform at long range. The BC on the bullet you choose will determine the trajectory and the wind drift on your bullet, if other factors such as velocity are equal. BC can also change with the speed of the bullet. Lastly, the shape of your bullet can factor in. A pointed bullet will generally have a higher BC than a round-nose bullet and a boat-tail bullet will generally have a higher BC than a flat-base bullet. This is due to shape and the reduction of the drag on the bullet.

The cartridge components should be match grade at minimum, meaning everything is identical. Every case is cut and sized the same, match grade primers, exact powder charge, and bullets seated to the exact depth. Exact means just that, EXACT. Don’t compromise if something comes out even one thousandth off or a tenth of a grain off. Fix it so you know they are all perfect.

I personally would only shoot my own reloaded ammunition for long-range shooting. I like to know my ammunition is exact round after round and the only way to do that is if I am the one making it. From sizing my brass, cleaning the primer pocket, cutting the casing to length, de-burring the neck, seating the primers, adding the powder, seating the bullet—I like to be the person responsible for quality control. The more exacting you are in the preparation of your ammunition, the more consistent your ammunition will perform for you at long-range.

My California buck taken at 867 yards with one shot

The Riflescope

Your riflescope will be a valuable investment to your long-range set up. I prefer the scopes with variable power with at least 14-power magnification. Much less than 14 power makes it more difficult to be precise at the longer distances. I personally shoot a 5x–20x power scope with a 50mm objective.

The size of the objective should be 40mm or greater. The larger objectives will give you more field of view for finding your target at long distances and will gather more light in low light conditions.

Also make sure your rifle has some type of parallax adjustment. Parallax is an apparent displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight, and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Parallax can certainly come into the equation when shooting long-range. Even a slight displacement from where your cross hairs appear to be and where they actually are can be the difference between a hit and miss.

The turrets on your scope should have the ability to be customized. There are several companies making scopes with custom turrets that will enable the scope to fit the specific cartridge you have loaded for your rifle. With a custom turret you can eliminate any holdover.

When looking at the turrets, pay close attention to the adjustment scale. I would recommend a rifle that has ¼” or 1 cm per click at 100 yards. This will allow you either 15 MOA or 20 MOA in one complete revolution of your turret. Generally that will get most modern calibers out to 800 to 1000 yards in one revolution.

If your riflescope isn’t capable of customization, no worries as long as your scope has MOA markings. Once you have all of your drop data figured out and your rifle is zeroed, you just make a cheat sheet. Your cheat sheet will just reference a specific yardage and indicate what MOA marking you need to turn your scope to so you are aiming right on your target. When I used this method in the past, I used a computer to print out the information in a very small font and taped it directly to my rifle.

Developing Your Drop Data

There are two ways that I have used to figure out my drop data:

- Exterior ballistic software

- Shooting my drop data.

There are several quality exterior ballistic software programs out on the market today. They are extremely accurate and many custom turrets are built directly off the data from these programs. You need to know the weight of your bullet, the ballistic coefficient of your bullet, the velocity of your bullet, your desired zero distance, sight height and your environmental conditions, such as temperature, altitude, pressure, and humidity. You input this information into the software and it will generate your drop data out as far as you would like. My experience has been that these programs are within a one or two clicks at 800 yards, which is roughly two to four inches from your point of aim. That is certainly pretty accurate.

The second method of shooting your drop data is fairly easy also, and is usually more precise because you are shooting the specific equipment you have developed for your long-range system.

Once you have zeroed you rifle at desired distance, pick an intermediate distance, such as 500 yards, and determine the number of clicks or the MOA. Then shoot a long distance, such as 1000 yards, and again determine the number of clicks or the MOA. With your zero, 500 and 1000 shot in, you provide that information to the company that is building your custom turret, along with all the information mentioned above, and your turret will come out exact out to a 1000 yards.

If you don’t have a custom turret and are using a standard turret with MOA markings, you can use ballistic software to figure your exact drop data. Input all of your specific information from above and calculate your drop data. If it doesn’t match at 500 and 1000 yards you will need to manipulate the BC on the software until the software calculations match what you shot in the field. This method will take into account that BC can change slightly from rifle to rifle and will also change as the bullet slows down at long yardages.

The reason shooting your own drop data is more accurate is because the software generally doesn’t take into account several variables: the actual BC of the bullet out of your rifle, both at the muzzle and at long distances, and the affects of your bullet transitioning from supersonic speed to sub sonic speed during its time of flight. I personally have shot both methods and the software is very accurate overall. If I were not so particular about my set up, I wouldn’t hesitate to use it.

This is where my buck stood. I took the shot from the very bottom of the canyon.

Environmental Factors

Temperature, altitude, pressure, humidity and wind will all influence your bullets impact at long-range. In ten years of shooting long-range, I’ve learned the influence on bullet impact is not that much overall, with the exception of the wind.

Your turret will be built to specific environmental conditions. If those change, you don’t necessarily need to have another built. I have found that if you are shooting a cartridge with a flat trajectory, you will be just fine out to about 600 yards. The reason for this is that if your turret was built at say 5000 feet and 50 degrees Fahrenheit. If you go on a hunt at 7000 feet, it generally is going to be colder and the lighter air at the higher elevation combined with the denser cold air nearly cancel each other out. This is generally the case at ranges under 600 yards and elevations that are within + / – 1500 feet of your custom turret.

Beyond 600 yards, you will need to take into account the environmental differences. To determine the differences, use the software and print out your drop data for your custom turret and then print another for the conditions of your hunt. Compare them side-by-side and make note of the differences at the longer ranges.

Wind is an environmental factor that is not an exact science. Wind is also the most difficult environmental factor to determine. The wind where you are shooting is probably not the same as the wind 1000 yards from you. Remember 1000 yards is over a half mile away, so you have to read the wind with your optics at your target location and compare it to your position.

Once the wind is determined, you can either use your windage turret to compensate or use hold off. I am not a big fan of using my windage turret in the field, so I would choose hold off under those circumstances. Again, your ballistic software can tell you your hold off for a given amount of wind. Some riflescope reticles will have 4 or 5 hash marks that represent one MOA each. This type of reticle is easiest as you are rarely holding more than 5 MOA of wind drift.

Calculating the wind is also another challenge. I use a wind meter, which is simple, but it only calculates the wind at my position. But if I look around where I am and take note of how the vegetation is moving and compare that to what I am seeing through my optics, I can make a fairly accurate measure of the wind. Also, the direction of the wind is important for determining how it will affect your bullet. If the wind is straight at you or directly behind you, the wind will not affect your bullet enough to compensate for. If the wind is directly from your right or left, compensate for the strength of the wind based on your drop data. If the wind is quartering to you or away from you, compensate half value based on your drop data.

Angle Cosine Indicator

An angle cosine indicator is a device that measures the angle at which you are shooting. The steeper the angle, the more you will need to compensate for it. Whether shooting uphill or downhill, you always take yardage off when compensating. I use an angle cosine indicator that mounts on my riflescope. It gives me a number between 100, being level, and 26, being nearly straight up or down. It works off a percentage by the number that is indicated once you are on target. For instance, if I am shooting 700 yards and when I am on target it reads 90, I calculate 90 percent of 700 and come up with 630 yards. This type is easiest for me personally, but there are angle cosine indicators that will give you the angle at which you are aiming and then you use a cheat sheet to determine how much yardage to take off.

As with the environmental factors, I personally don’t worry about the angle unless it is really steep uphill or downhill or I am over 500 yards.

Optics

When shooting long-range, optics can’t be overlooked. A quality spotting scope can save you a lot of walking to check your targets. Whenever I am at the range, I practice not only my shooting, but also my wind estimation. The spotting scope is perfect for watching the environment at your target and comparing that to what you see at your position.

I also use quality binoculars in the field too not only locate game, but to spot for my hunting partner when he is shooting. Having a spotter is critical if you have to make a follow up shot. At long-range you will not be able to see or hear your bullet hit its mark, so your spotter needs to call the shot for you and give feedback as necessary.

Rangefinders are mandatory for shooting long-range. If you don’t have one, my opinion is you shouldn’t shoot anything long-range. When deciding on a rangefinder, get the best you can afford. Rangefinders with at least 1000 yards and work under a variety of environmental conditions are preferred. You should do some comparisons if you can. Many rangefinders will only work at long-range with perfect light conditions or don’t work well with rain, mist, fog, or snow.

Custom Turret pictured after the shot

Rifle Rests

After all the time you have put into getting your long-range set up just right, don’t forget you are not shooting off a bench in the field. Having a rock solid rest is crucial once you pass the 400-yard mark.

There are several ways to get your rest rock solid in the field. First off I would prefer to shoot in a prone position every time if I can. When you are shooting prone, you will have a lower center of gravity and more points of contact on the ground. If you can’t get prone, try sitting then kneeling. I would not recommend any off-hand shots at long-range, no one is that good.

I will shoot prone using my backpack for a rest or using a bi-pod for a rest, or both. I have also taken small nylon bags into the field with me and once at my hunting location fill these bags with loose dirt. This would make a pretty good improvised sand bag. You can also try shooting sticks for sitting or kneeling or utilize the environment around you to create a rest. Whatever equipment you are going to use in the field, you should also practice with at the range. At long-range your rest is critical to accuracy, so have a solid one.

The Final Set Up

After deciding on all your equipment, caliber, bullet, optics and your rests, it is time to put it together. This has to be done on the practice range before it should ever go into a hunt. If you can’t consistently make the shot in practice, then it is too far to take into the field. You can easily find your maximum effective range by how well you perform in practice. If every round hits the mark in practice from all your field positions and improvised rests at a given distance, then you have found your maximum range. It may not be as far as you would hope initially, but you can increase that number with practice, practice, practice.

A minimum standard to strive for with long range shooting is 1 MOA for every 100 yards of distance. So at 100 yards I should shoot a 1” group, at 500 yards a 5” group and at 1000 yards a 10” group. If at the practice range you can hold this standard at 600 yards, but at 700 yards it opens up, limit your self to 600 yards. The more you practice and fine tune your equipment, the higher that number will go.

Long-range shooting at the practice range can be fun and challenging. Get into this with a friend and make the shots worth something, this will build in some pressure to perform. This will help when it counts in the field. One last comment on long-range shooting, be honest with yourself when it comes to your maximum effective range. If you lie to yourself about your abilities you will ultimately make poor decisions in the field and take shots that will end up with less than desirable results.

Putting It to the Test

Opening day of rifle season 2009 found me and several of my long time hunting partners in our same hunting area we had been to for the last 15 opening days of rifle season. We were hunting about 10 miles into one of the Northern California Wilderness areas and have always had pretty good luck as a group. One of my friends, Ryan, and I went into one particular canyon and started glassing from our usual spot. It didn’t take long to start finding several bucks, but we also found many hunters in the same canyon. This had been fairly normal for us over the last several years, as many more people started in on the DIY type hunting style.

Ryan and I glassed one buck I had seen in archery season, a nice 4 x 2. The buck was basically a big fork with small forks on his right side. With all the other hunters nearby, it was shoot or have this buck shot out from under us. Ryan decided to shoot and with one shot at 650 yards the buck was dead in his tracks.

We continued to glass and within minutes Ryan located another shooter buck. I took one look at him through the spotting scope and decided I better take him. This buck was walking in a spot that other hunters were surely going to see him soon. I took careful aim and fired, the buck dropped in his tracks. That shot was my farthest at 867 yards.

Ryan and I had no doubt our shots would find there mark. We had all of our equipment dialed in for long-range hunting. Our rifles were custom made, our ammunition we reloaded with the tightest of tolerances, we had custom scopes with Ballistic Compensating Turrets, laser range finders and rock solid rests.

My Long Range Set Up

Rifle: Custom .300 Jarrett

Scope:Huskemaw 5-20 x 50

Turret: Custom by GunWerks

Spotting Scope: Swarovski STM 20-60 x 65

Binoculars: Swarovski 12 x 50 EL’s

Rangefinder: Zeiss Victory

Tripod: Outdoorsman Medium with Pan Head

Bipod: Stoney Point Rapid Pivot Bipod – Prone

Angle Cosign Indicator: Sniper Tools Design Company

Wind Meter: Kestrel 2000

Ballistic Software: Best of the West

Cartridge: .300 Jarrett (8mm Rem Mag necked down to .30 cal)

Primer: Federal GM210M

Powder: Reloader 25

Bullet: 210-Grain Berger VLD

Velocity: 3000 FPS