The fog would allow us to drop down into the snowy gash just below the summit without being seen. From the rocks on the other side, we’d have a view of the goat from maybe 250 yards.

That was the plan, and the plan wrongly assumed the fog appeared and would disappear with our wishes in mind.

Hunting In The Fog

It took ten minutes to pick our way down the mountain to the gash and stand on the last remnants of snow. We walked timidly, not knowing how much of the snow had been eaten away by the flowing water underneath. It seemed we were five or so feet off the ground. How much of that was actually snow made me nervous.

Serrated Ridge

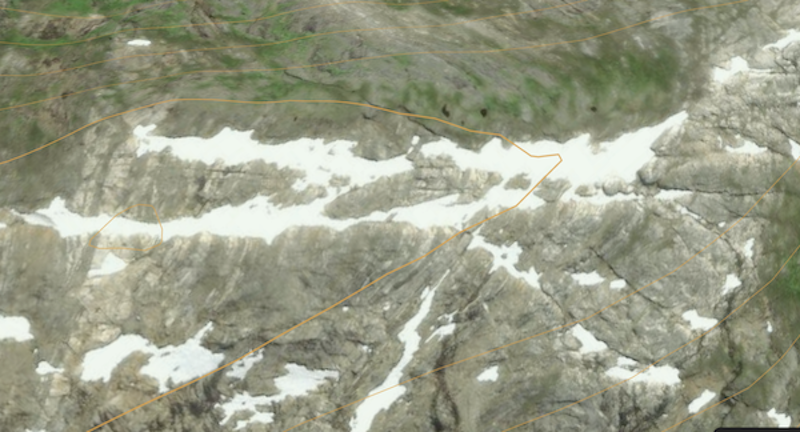

Few ridges in the Southeast Alaskan landscape are a simple joining of two slopes. The jagged nature, especially in goat country, of the mountain tops makes for a frustratingly exposed, not to mention slow, pace. We often find ourselves zigzagging through gashes in the mountain so the track looks like a series of switchbacks. Topographical maps make the terrain look steep but relatively benign. Satellite photos provide a better picture but don’t tell of the brutality. Stripes of snow that cross the ridge indicate notches that hold snow for most, if not all, of the year. These gashes can range from a few to 30 or 40 feet deep.

Sometimes, the only move you have puts you in view of what you’re trying to stalk. Sometimes, the only way across without being seen is to cross in a fog that is thick enough to hide the movement but light enough you can make safe passage. This should only be done when you can scout where you’ll end up. Getting across or down a tricky spot can put you in a worse spot that won’t allow you to retrace your steps or climb back out. The fog and mountain sucker you into a call on the inReach.

Safely Forward

The fog thickened, so when we crested the other side of the gash, all we saw was a large, clover leaf-shaped area that looked like a miniature reservoir that had been drained. Bright green moss grew at the edges. It was a shocking contrast to the jagged rocks we had just traversed. It looked like we had been transported from mountain goat terrain to tidal flats. We walked across the flat, covering way more ground than I thought would be possible. I hoped to shave 75 to 100 yards, then relocate the billy and decide what to do. We had been able to move double that, which was great, but the fog wasn’t relenting.

On the far side of the reservoir, we stopped. We were within striking distance, way closer than I thought we’d be, but the fog sat. It wasn’t moving in endless sheets born on a stiff wind. It was floating lethargically, hauntingly. It lured us in, but now we were stuck.

Test Of Patience

It started to rain, and my irritation became frustration. I deployed my tarp, and my wife and I hung it over us like a blanket. The light raindrops hit the fabric and pecked at my remaining patience. There was no way the billy would still be there. I don’t have that luck.

A few weeks earlier, my wife and I had stalked a deer and a goat crested at 75 yards. She only needed one shot, but the goat fed off the cliff and was gone. That seemed to be our luck for the year.

All Is Lost?

After a long, foggy wait, I repacked the tarp when the rain stopped after 20 or so minutes. A feeding goat can cover a lot of ground in that time. I thought it was gone. To make things worse, I didn’t know exactly where we were. We were surrounded by mounds. The wind told me the direction, but we had to find the exact line we took to get back up and around the summit, then down the ridge and wrap around to camp two miles away. It was mid-afternoon, and wandering off the wrong edge was a possibility if we kept moving blind.

The fog relented enough for us to get our bearings. We were where I thought we were and pretty close to where the goat should have been, but we didn’t see it. Our stalk had given up the high ground, and I had expected to see the goat feeding in one of the depressions we could now see in front of us, 75 yards out. The fog loomed, but not as thick. However, my attitude did not improve. I didn’t want to get suckered into going further down the ridge.

It’s always a risk moving in the fog. We had made a calculated decision to traverse two known mountain features and hang tight. Any more, and we’d be pushing our luck, especially given the time of day.

“It’s gone. There’s no way it’s here.”

“It has to be here. We’ve come all this way. Check over the edge,” my wife prodded back.

I felt like a pouty little brat being so discouraged, but my wife was right. Twenty more feet up a small knob wasn’t crazy or irresponsible. Crest and I’d see what I could.

The goat wasn’t there.

I was right.

Hard To Stay Positive

I felt a little bad because I knew it was probably difficult for my wife to stay positive with me so crestfallen, but positive she stayed. She had taken her goat a few weeks ago; now it was my turn, and everything had fallen apart.

To make sure, I walked along the edge of the lip, completely exposed to anything in the depression below us but likely too obscured by the fog for anything to immediately spook since the wind was in our favor. I took the last breath of the day’s hunt. It was the heavy maybe-we’ll-see-something-on-the-way-back-to-camp breath.

All Was Not Lost

That’s when the billy rose from its bed. Abby was right. Off by 20 yards, but right. It was still there. I turned to her in shock. She seemed as surprised as I was

The billy stood, processing what we were. I lifted my rifle and took the second standing shot of my hunting life. The billy reared, stumbled down the lip, and collapsed. Knowing these animals are extremely tough, I followed and chambered another round. I told Abby to stay put so we wouldn’t lose track of our packs—I had stopped our stalking track to save my phone battery and didn’t trust my GPS in the fog.

The billy returned to life and attempted to stand. I fired another shot into his lungs, and he rolled to the bottom of the depression.

The fog started to lift, and by the time I stood over the goat, we could see all the way down the ridge, past the mountain, across the inlet, and to the peaks on the far side.

The weather broke…until we started the 2-mile hike back to camp.

Lessons

Never move in the fog. It’s not worth it.

That’s the only advice that can really be given since anything else could become justification for someone else to press on and later push the SOS button.

There has to be a fairly clear boundary for acceptable risk. Fog doesn’t let you plan, scout, or discuss options. You get part of the story. Sometimes, it’s enough to make a prudent guess. Other times it suckers you in.

Experience Is Important

It often comes down to experience. Thunderstorms, tornados, and wildfires terrify me when I am hunting or backpacking in the Lower 48. I have little experience, so my frame of reference is what I’ve seen reported on the news. But I grew up hiking in the rainy, foggy Southeast Alaska climate, and it’s made me conservative, not bold. Weather breaks offer tremendous opportunities but are laced with misery. That’s the rub. But by hunting them often, I’ve been able to experience the bewilderment brought on by elements such as rain and fog.

Though I am prone to frustration, I have hard limits when it comes to how a situation makes me feel, and I am much more likely to quit and pout than press on irresistible. But those are by Alaskan standards, and standards vary by location and experience.

Additionally, my wife and I had a photograph of the goat and the terrain between us to give us an idea of where we were going as well as the distance. We had also seen both sides of the mountain and knew just how severe the consequences were should we drop off the jagged yet lush, slightly-rounded ridge. We couldn’t see, but we weren’t blind.

That’s how I’ll justify our move, and I’d do it again.

With a better attitude, of course.

You can ask Jeff questions or comment on this article here.