Mule deer have been studied intensively the last 50 years. While we don’t know as much about the species as we do whitetail deer, we do have a body of evidence to draw from that can help make us better hunters.

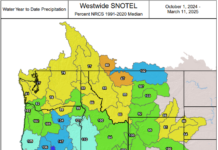

I attended a mule deer symposium in Missoula, Montana in 1998. It was a collection of biologists, researchers, and various officials from game & fish agencies from around the West. We were still reeling from the winterkill of ’92/’93, so hard winters were a hot topic.

One of the keynote speakers was researcher Richard J. Mackie of Montana State University. He was presenting on his then recently released research project titled “Ecology and Management of Mule Deer and Whitetail Deer in Montana.”

I learned something from him that day that I’ll never forget:

When mule deer populations shrink substantially—like after a bad winter—in the following years the remaining population occupies mostly the highest quality habitats while largely vacating less desirable habitats. If mule deer populations begin to increase, more deer will move into those less desirable, formerly vacated habitats.

In laymen terms, that means some areas will hold almost no deer after winterkill.

I’ve witnessed this in the foothill country east of my hometown of Iona, Idaho. This is lower elevation country mostly void of the rougher terrain that big bucks are attracted to. It’s dry-farm (no irrigation) and mostly lacks the green highly nutritious shrubs, herbs, and forbs that deer need to grow fawns and big antlers. It’s also got too many roads to serve as a sanctuary and more often than not holds few deer and even fewer big bucks. However, when mule deer populations are relatively high or peaking, I find more than a few deer and even a few big bucks using this habitat. My experience in this area seems to mirror what Mr. Mackie had observed.

Mr. Mackie’s observations have since been confirmed by other researchers, including Dennis D. Austin, research biologist for the Utah DOW in his book, “Mule Deer: A Handbook for Utah Hunters and Landowners” (I’ll be reviewing his book soon on the Rok Blog), so I know this is not an isolated phenomenon.

For the Intermountain West units that I hunt, the highest quality habitat is typically the aspen/conifer zone (which by the way often grows the biggest bucks, but that’s a topic for another blog post.) The least productive habitat is usually desert country. There are many exceptions—like burns, certain agriculture, sanctuaries, and microclimates— so the only sure-fire way to find them is by scouting and hunting.

If your area was hit with significant winterkill, look first to the highest quality habitats for deer and big bucks. Every state and even unit is different, so you have to draw on your own experience or do some research. A local biologist should know the most productive habitat types for deer and big bucks.

This post wraps up this series on hard winters (if you missed anything, see Bad Winter? Now What?, Hard Winter—Spring Update (and podcasts!), What Really Happens to Big Bucks After Hard Winters, Bucks I’ve Taken After Hard Winters).

As spring picks up speed, I’ll be blogging on mule deer books, clothing for the mule deer hunter, winter range bucks, and why I still have a file cabinet for researching big mule deer.

See how I research mule deer hunting in my book, Hunting Big Mule Deer