Arrow Dynamics: Sensibly Choosing FOC

By Daykota Kime

For a group of individuals who pride themselves on the simplicity of a “stick and string”, we sure have a tendency to get lost in the details of it all. Front of Center (FOC) has become to the archery world what Keto or Paleo has become to the health world. A fashionable term, in which those who use it the most seem to have the least amount of understanding of what it is or how it works. That’s not to say this concept doesn’t have some merit, so I’ll do my best to offer some context. High arrow FOC has shown benefits in downrange accuracy, energy retention, resistance to wind drift, penetration through heavy bon (and if you try hard enough, it may even increase your sense of well-being.)

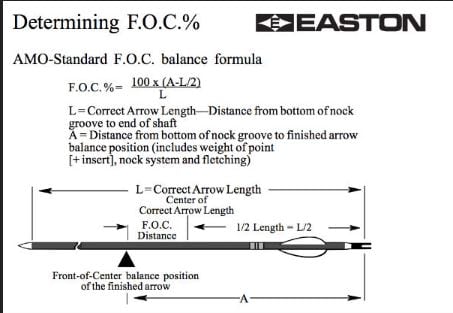

All kidding aside, I’ll do my best to explain what it is I’m talking about here. Grab an arrow and place your finger in the middle attempting to balance the shaft on your fingertip. More likely than not that arrow is going to lean toward the point end of that arrow shaft. This is because the front half of an arrow typically weighs more than the back half. So using the magic of schoolyard seesaw science, we slide our finger closer to the front of the shaft until we find a point in which the shaft balances evenly. How far forward do we move from the center of the arrow? Commonly it is anywhere between 10-15% depending on your FOC

Simply put; we are attempting to figure out how far in front of center the balance point of an arrow is. The higher the number, the further in front of center your balance point will be. That distance is directly correlated to a number of factors that have more to do with weight than length, but shaft length is an important factor. Shaft weight per inch and the weight of all other components that go into building an accurate arrow have an effect on the FOC, just as FOC has everything to do with building an accurate arrow.

Building an Arrow

“Why do I even care about front of center percentages? Shouldn’t I just put more weight up front and call it good? I’ve read the Ashby reports and he has stated that anything less than 30% front of center will be detrimental, shouldn’t I follow his word?” or so the critics go…

Let’s back up a bit and take a look at some of the components that go into an arrow to gain an understanding of some foundational ideas. The number one item Dr. Ashby (listen to the man himself on Kifarucast here) and others have attributed to arrow penetration is an arrow’s structural integrity. Arrow shafts are produced by a variety of manufacturers. Putting aside names and camo patterns, they all have one thing in common and that is that they are offered in various spine sizes (deflections in engineer speak). Typical arrow spines ranging from 500-300 and even up to 250 and 200 spine arrows are not uncommon today. But what does that number mean?

Spine is a measurement of the stiffness of an arrow, or how flexible the shaft is at rest. The standard test for arrow spine is to suspend a shaft 29” in length between two supports that are 28” in separation; an 880 gram (just under 2#) weight is hung from the center of this shaft. The amount that shaft bends is known as static spine. So a 500 spine arrow will deflect .500” a 400 spine will deflect .400”, and so on and so forth–so the lower the number the stiffer the arrow. This is a simple test that has become the standard for all arrow manufacturers across the industry.

“Great! But what does that have to do with my arrow FOC?”

We’re getting there, don’t worry. When we take an arrow, build it into a finished product, and send it down range, we are not hanging a two-pound weight from the center of it. Instead, the force applied to the back of an arrow when it is released causes the arrow to bend and flex yet again. This reaction is called dynamic spine, and refers to the amount of flex an arrow has during flight. Dynamic spine is a product of the amount of force applied to the back of the arrow by the bow. This is the amount of flex an arrow has as it is being launched from your bow.

For those of you who have never witnessed an arrow bending upon release, feel free to cruise through Youtube and search Archers Paradox on a Recurve Bow. You will notice that when shot, the arrow shaft bends out of the way of the bows plunger (rest) and appears to “snake” back on target by the time it is no longer attached to the string. Proper dynamic spine has a direct correlation to consistent arrow flight, broadhead tuning, and achieving a forgiving arrow setup.

Draw weight, draw length, and how aggressive the cams are (shown through higher FPS), the shaft length, the static spine of the arrow, and the amount of weight that the components that make up the rest of arrow (nock, point, insert, vanes, etc) all contribute to how much dynamic spine you may have. To think of this in a simple way, imagine grabbing a 10-foot length of PVC pipe at one end but at the other end is a five-pound weight; that piece of pipe is going to bend and whip like crazy or even potential break in half. But what about if that pipe were only one-foot long? Very little whip, same pipe, same weights–a completely different reaction.

Real World Application

“Okay, that makes sense but how is this helping me as a bowhunter?”

Seeing as how most of us don’t have the luxury of access to dozens of arrows in various spines and point weight combinations, we have been forced to purchase whatever the archery shop has to offer us. Fortunately, manufacturers have produced arrows in these spines with an assumption that you are going to use their standard insert and a 100-grain broadhead up front. They have done this because it is a safe way of covering most bowhunters setups to perform okay at standard draw weights. In most cases, a 60# bow is recommended to have a 400 spine arrow, a 70# bow would use a 340 spine or depending on cam aggression, a 300 spine. Take the average hunter who is going to shoot a three fletch, two-inch vane setup in the back with a factory nock and you have an arrow capable of killing North American Big Game.

“Perfect! I shoot 70 pounds, I have a 340 spine arrow, I can shoot 315 grains up front!”

Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way. We cannot suddenly start shooting more point weight because you want to increase your FOC percentage without taking dynamic spine into consideration. When we manipulate our front of center percentage, what we are doing is tuning the dynamic spine of a particular arrow shaft to its optimum forgiveness for our setup as a bowhunter.

Let’s look back at our PVC pipe again, if we want to add more weight to the front to increase FOC we have to find a way to make the pipe stiffer or else it will keep bending. How do we increase the stiffness of our arrow shaft to handle the heavier point weight that we are attempting to put up front?

We can…

- Shorten the arrow shaft similar to the first PVC example

- Increase the spine of the arrow shaft itself by purchasing a different size

- If fine tuning and you have the ability and understanding, increase the amount of fletching or weight on the rear of the shaft.

- Any combination of the previous three options while manipulating bow poundage.

Option one is normally the easiest option if you have the luxury of a few extra inches of arrow to chop off. This is not only the cheapest option because you don’t have to purchase new shafts, but also it eliminates the added shaft weight that comes with increasing an arrow size. As we shorten our arrows, we shorten leverages that act on the arrows as well. If you have ever used a cheater bar on the end of a wrench, you’ll recognize what I’m talking about.

Option two is a bit complicated because although it may allow you to shoot a heavier broadhead, it is also not going to increase your F.O.C. percentage as much due to increased shaft weight. Our balance point is a ratio of point weight and excess to shaft weight and excess. Arrow manufacturers manipulate arrow stiffness by increasing the wall thickness of the arrow shaft itself; this increased thickness increases the weight of the shaft. Playing the FOC. game is a balancing act of optimizing shaft weight with the right broadhead weight to achieve the forgiveness and percentage you are comfortable with.

Option three If you really want to get caught up in the weeds, you can fine tune arrow stiffness by shooting a variety of different vane combinations. By changing vanes combinations, you are changing weight on the rear of the arrow and which is either going to slide your balance point forward if you remove weight or rearward if you add weight. This directly affects the spine of your arrow because the further away that balance point is from the end of the shaft; the more leverage the end of the shaft and the fletching have to direct the arrow.

Option four is best skipped for now as it is fairly intensive.

“So why not just shoot the stiffest arrow I can buy and load that thing up front? Super stiff, High FOC, I’m on my way to double lung city!”

You could definitely do that, and most of the time we recommend that people error on the side of slightly stiff rather than slightly weak. The issue with arrows that are too stiff is that they don’t lend themselves to being “forgiving”. Remember that Youtube video from earlier? The arrow flexed and twisted, all the while staying on target. Super stiff arrows don’t have this advantage of resisting crosswinds, nor other external factors, while keeping the point on target. This stiffness makes them more prone to planning than one that can flex the proper amount.

Wrap Up

“I’m officially confused, what exactly are you telling me here?”

High FOC percentages are a good thing, but they are not close to the only thing. As bowhunters, we all strive to be as accurate as possible in hopes of seizing whatever moment presents itself to us. No magical percentage is going to get you on the cover of your favorite magazine or fill your walls with the trophies of a lifetime. However, FOC does have its place in our world.

Even the biggest proponents of high FOC have listed structural integrity and arrow flight as more important factors than hitting a certain percentage. Sacrificing either of these for the sake of increasing a percentage is a detriment to your arrows performance. Manipulating FOC is a tuning technique, not a goal. High FOC arrows are a byproduct of arrows that are well built for the task at hand.

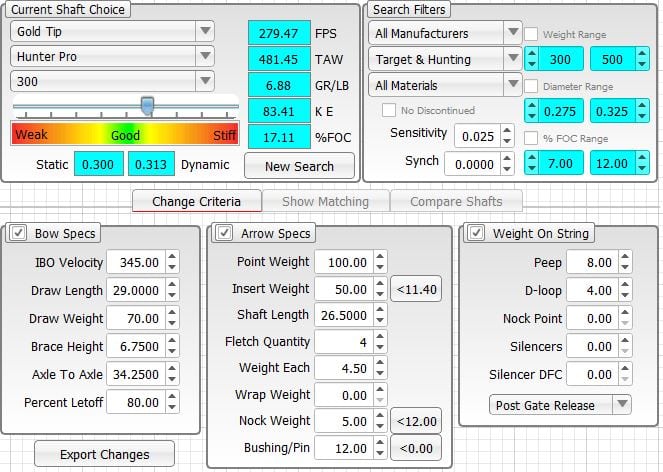

Ontarget and Archers Advantage both offer software in which you can input your bows information and select arrows based on point weight or any other variable you want. It will provide you feedback that will get you into the ballpark in terms of your arrows proper spine reaction. Based on my personal experience with these programs they are accurate and offer valuable feedback to display your finished arrow weight, FOC %, and estimated arrow speed.

Again, high FOC arrows are a great tool to have and they allow us to understand our equipment more intimately. There are many different ways of which we can address this subject; my intent was to hit a few of the high notes without diving too far into the details.

Before you go sacrificing forgiveness and arrow stability for the sake of a high FOC, remember that proper flight of a durable heavy arrow and a high degree of shooting ability will win every single time.

You can comment on this article or ask Daykota questions here.