Synthetic Insulation Technology for Hunting

by Dave Chenault, Rokslide Member

Synthetic fill “puffy” jackets are rightfully common in the backpacks of hunters. Aside from down, these coats provide more warmth for the weight than any other option and, unlike down, they provide this warmth with modest bulk, and good resistance to both internal and external moisture. Recent developments in synthetic insulation have made for even more options for hunters, but for the hunter not versed in the details of insulation and fabric speak, it can be difficult to tell the differences and figure out which kinds of jackets work best for what.

When contemplating a new puffy and trying to figure out how it will work and how warm it will be, three pieces of data are essential: the insulation type, the insulation weight, and the air-permeability of the shell fabric and liner. I’ll examine each in turn before moving on to different examples of puffy jackets from the hunting and “mountaineering” world, and the sorts of hunting to which each is best suited.

Lead Photo: Author glassing for black bears in early May, wearing the Rab Strata jacket with Polartec Alpha insulation. The Strata does a good job allowing sweat to evaporate through the fabric and insulation, and therefore works well for keeping you dry during long days with strenuous hikes between glassing sessions. The Strata also has high-quality construction and a well fitting hood.

Synthetic insulations try to mimic down’s still un-rivaled ability to trap air and hold heat. It doesn’t take many days in the woods, especially the rainy and sweaty hunting woods, to realize that there is a lot more to staying warm than just trapping air. Down clusters attract moisture, give up that moisture slowly, and because they have to be sandwiched between dense fabrics too keep the feathers in place, drying is made even more difficult. Treated down improves the first two issues to a certain extent, but cannot help the third, and in my limited experience synthetics still deal with moisture significantly better. In theory down is warmer for the weight than all synthetics, but in practice is often colder, especially in the hunting world.

The various types of Primaloft have been around for decades, and are the standard by which all synthetic fill insulations are measured. Primaloft still lab tests the best of any, but one of it’s main advantages is how little thickness is needed for a given level of warmth. Loft and insulation value do not correlate one to one with synthetic fills, and a mid-weight Primaloft jacket (with 100 grams/meter insulation) might be a third as bulky as a down coat with similar warmth. This is an obvious bonus for hunters who need to slip through brush and shoot a weapon with minimal interference from their jacket.

The downside of Primaloft is the considerable extent to which it looses warmth with use. If you ever tear the shell fabric of a Primaloft coat, you’ll see that the insulation (mostly) stays put. Primaloft comes from the factory as a continuous layer of batting, with interwoven layers of fibers forming a series of thin sheets which are held together by scrim. During the course of normal use, such as stuffing the jacket into your pack or sitting with your back against a rock, these fibers break down and the ability of Primaloft to trap air degrades. I don’t have an intimate understanding of the mechanics, and companies are unsurprisingly silent on how quickly this happens, but my anecdotal experience agrees with a few of the numbers I’ve seen thrown around: Primaloft can loose 30-40 percent of its insulating value in six months of frequent use. In two years of heavy use a Primaloft coat can be quite cashed out. By contrast, a down coat which is washed reasonably often can easily last a decade, maintaining the same level of warmth throughout.

Climashield insulation, the most current version being Apex, goes a long way towards solving Primaloft’s durability problem by being built from more robust sheets of material (“continuous filament”). Unlike Primaloft it does not require scrim or extensive stitching to keep it in place within a garment. While Climashield will degrade and eventually wear out due to cumulative flexing and compression, it resists this several times better than Primaloft. The reason Apex is more common in sleeping bags/quilts than clothing is that Climashield is bulkier and less flexible than Primaloft. This is a downside for particularly light and thin layers which might be worn while moving, as well as for fashion, but for a durable and fairly long-lived synthetic hunting coat, Climashield is hard to beat. It lab tests a bit colder than Primaloft of the same weight, but after a few months of use this difference will likely be erased.

Because of the stable Alpha insulation, the Strata can use mesh for substantial portion of its liner, which promotes moisture transport but also reduced the jackets ability to trap air, and thus heat.

Unfortunately, thing are not as simple as selecting either Primaloft for low bulk or Climashield for better life. For one, the insulating value of a garment, as well as other performance characteristics like durability and quietness, are determined by the fabric used both outside for the shell and inside for the liner. Primaloft and, to a lesser extent, Climashield, both require a certain density of shell and liner to keep tendrils of the insulation from peeking out, not unlike down. Such dense fabric adds insulating value by preventing air movement, while at the same time slowing moisture movement and thus dry time. Typically to make lighter fabrics insulation-proof, they must be densely woven, and often lightly coated (typically with polyurethane). This often adds substantial warmth, with the cost being a loud and crinkly texture. It is possible to make a synthetic jacket whose shell is both quiet and insulation-proof, but the cost is increased weight. With current technology, one thing out of the trio of quietness, light weight, and insulation-proof must be sacrificed.

The way insulating garments with dense shell and liner fabrics (both synthetic and down) inevitably trap sweat has been an intractable problem until recently. Polartec Alpha and the various copycats are a third type of synthetic fill insulation, one which offers particular value to hunters. Alpha et al are best understood as halfway between Climashield and fleece, with a matrix of synthetic fibers woven into a lofty and durable layer of batting. Alpha is unique is that it does not need a dense fabric to keep it together, which allows more breathable shells and liners. These more breathable fabrics are often pretty darn quiet while still being light. Breathability does not theoretically equal less warmth under all circumstances, but under the vast majority of field conditions it does. Alpha jackets are fantastic for stop and start movement in cold conditions, but even with a wind-stopping rain shell worn over top, they’re still not as warm as Primaloft or Climashield garments of similar weights. The future of Alpha jackets will be in balancing breathability and wind resistance, probably with different shell fabrics in different parts of the garment.

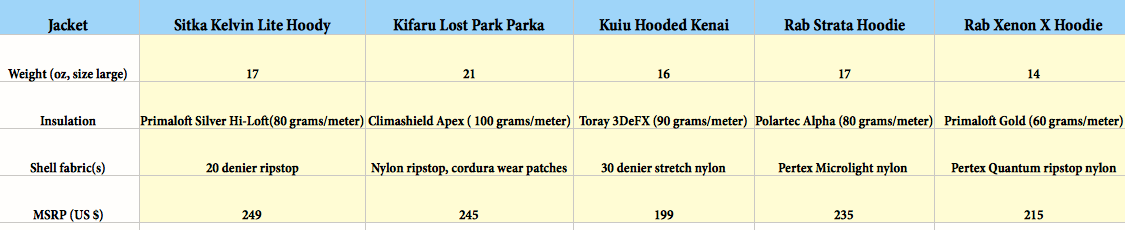

There are a bunch of excellent synthetic insulating jackets available to hunters, both from hunting-specific and outdoor or mountaineering companies, with a few examples in the chart above. Which one you pick will depend on your priorities and preferences. If absolute warmth, mostly while static, is primary then either the Sitka Kelvin, Kifaru Lost Park, or Rab Xenon X are the ideal choices. The Rab is one of the lightest synthetic insulating jackets available anywhere, and packs down small. It has the lightest shell fabric of any jacket listed above, and will be the least durable and the loudest. It is the best option for the weight weenie rifle hunters, and the worst option for the bowhunter who will occasionally stalk with the puffy jacket on. The Kifaru will be warmer and tougher than the Xenon, both in terms of insulation life and shell fabric, while the Sitka splits the difference between the two.

The Rab Strata and Kuiu Kenai are different creatures, and are suited to different applications. I’ve been using a Strata for the past 8 months, and have been impressed with its versatility. The way it balances warmth and breathability, and the way it moves sweat away from inner layers when used for shorter rest or glassing breaks, is truly impressive. One day this past November, hunting mule deer on a sunny day which never got above -10F, comes to mind. With only hat, gloves, a thick baselayer, and the Strata I was able to keep warm and dry through a full morning of steep hiking and glassing, until a deer walked out on a logging road 100 yards away and I filled my tag. In serious cold, staying dry is the key to staying warm, and I’ve never used any jacket which made this so easy.

Due to their lack of warmth, I’d have a hard time picking something like the Strata as my sole insulating layer for a backpack hunt, unless that hunt was in very cold conditions when I might bring the Strata for moving and something like the Xenon to wear over it when stationary. I suspect that a jacket insulated with Alpha would probably work well for riding horses or ATVs, as well as being an excellent day hunting piece. These jackets are best conceptualized as particularly warm, light, and effective soft shells, which may not look top-shelf on paper but shine in the field because they are effective and comfortable across an impressively broad spectrum on conditions, and can drastically reduce the frequency with which clothing changes will need to be made.

The Strata has nice long sleeves which stay put under all conditions, but the cuffs are contoured such that they puff out, which causes problems when doing things like shooting a bow and gutting an animal. Hunting-specific jackets should pay better attention to such things.

Being an informed consumer is crucial to selecting a synthetic insulating jacket which will work well for your style of hunting. As detailed above, different insulation types will have different performance attributes, as will different shell fabrics. Though manufacturers occasionally like to pretend otherwise, there are no miracles, shortcuts, or mysteries involved in insulation. Warmer jackets require more insulation, and particularly light and windproof shell fabrics will necessarily be loud and fragile. 60 grams/meter Primaloft jackets like the Xenon have become ubiquitous in recent years, and the low weight and bulk are attractive, but these jackets just aren’t that warm. In colder climates they are 1 or 1.25 season jackets only, with 100 grams/meter insulations being far more practical past late summer. Mountain companies have historically led the way in terms of new fabrics and the best warmth to weight ratios, but generally at the cost of reduced durability, increased noise, and less than ideal features and patterning (ex: cuffs which get in the way of a bowstring). Buy smart and a synthetic jacket will be a constant and welcome companion on all your hunting trips. Buy stupid and you’ll be cold, damp, and poorer for no good reason.

Dave Chenault is a lifelong outdoorsman who has been seriously involved in rock climbing, endurance mountain bike racing, packrafting, adventure racing, and most recently backcountry hunting. He is a staff writer at Backpacking Light and his words and photography have been published in Adventure Cycling Magazine, Trail Groove, and other places, including his award-winning blog bedrockandparadox.com. Dave lives with his wife in Whitefish, Montana where he works as a social worker.

You can discuss this article or ask the author questions here